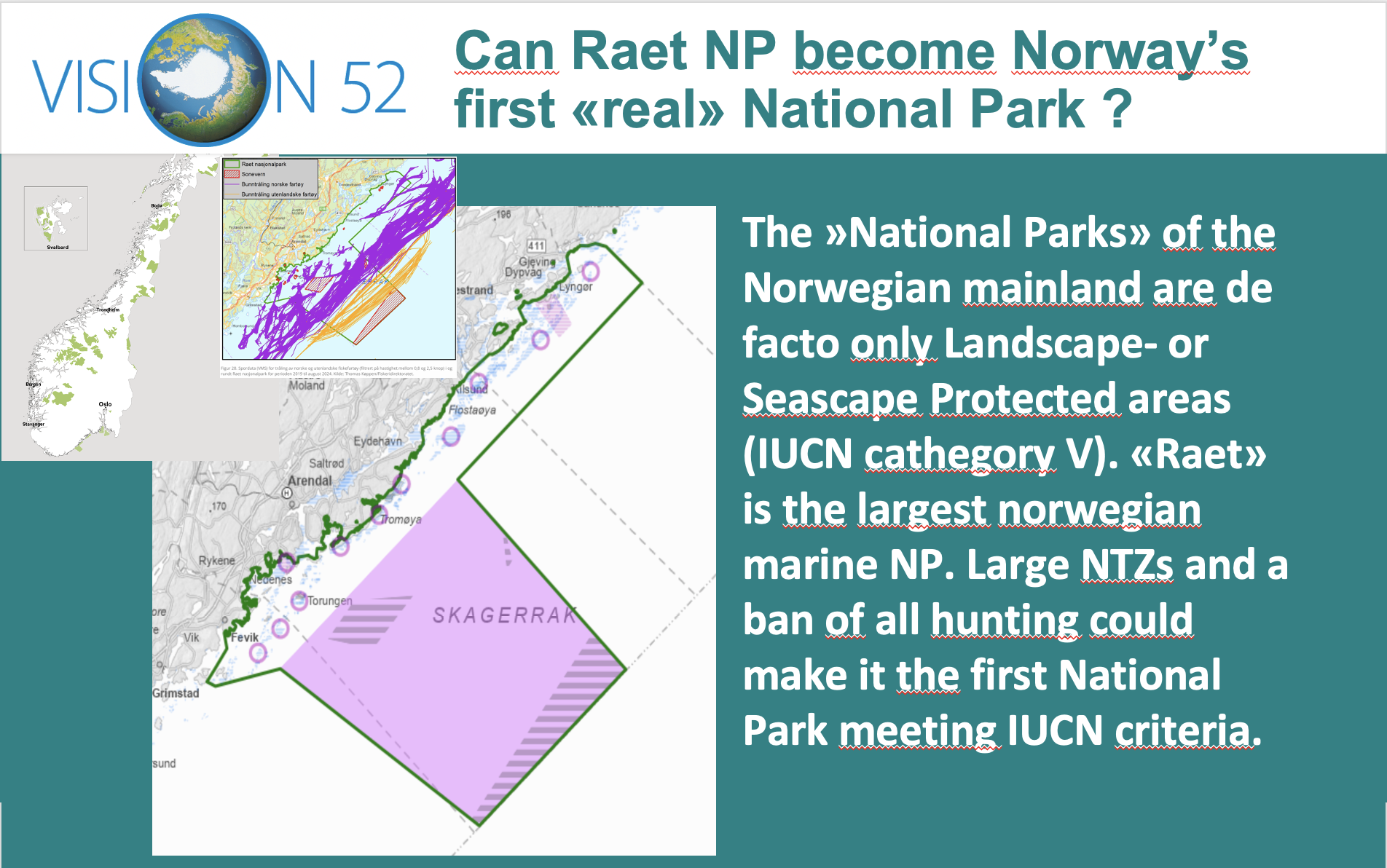

Norway is one of the world’s leading supporters of the United Nations and its Environmental Programme (UNEP). It has been among the main promoters of the 30 x 30 goal, that by 2030 30% of the global land and marine spaces should be effectively protected. On the other side, the country on its mainland so far has not been able to establish only a single national park, which meets international standards. Apart from Svalbard all their so-called “national parks” only meet the IUCN criteria for a landscape protected area. In all of them, hunting is allowed, and keeping farmed animals in the terrestrial parks is prioritized over allowing carnivorous mammals to enter the territory. In the few marine parks large-scale fishery of all kinds is permitted and significant no-take-zones are missing. Meanwhile, there are increasing voices in the country that this should change, and a competition of local communities about creating Norway’s first “real” national park could take off. In this respect, the marine “Raet National Park” at the Skagerrak coast in Southern Norway has a chance to win such a competition. VISION 52, as a member of the advisory council of Raet National Park, has recently described a way how to achieve this goal.

The full text of this input is available both in Norwegian and English on this website.

Furthermore, you find here a presentation, recently shown at the East Atlantic Flyway seminar on Langeness in the Wadden Sea, about the positive effects of no-take-zones in marine protected areas, including 12 examples from different parts of the world, where no-fishing zones have been in the beginning introduced against protests of local fisheries, where later the same fishers and local people got convinced about the positive effects of such protection measures and became advocates for no-take zones.

Only two major development measures are required to become Norway’s first “real” national park, and there are good reasons why they are easier to implement in Raet National Park than in other areas of Norway:

A) End all hunting throughout the national park.

Many countries around the world have experienced the so-called ‘national park effect’, which means that animals lose their fear of humans when hunting ends, thereby expanding their habitat and becoming an accessible attraction for visitors. Over the years, I have been able to study this in the Wadden Sea and demonstrate it to others using common seals and brent geese.

Danish ornithologist Hans Meltofte has analysed thousands of data points from around the world on the flight distance of waterbirds from humans and boats in areas where waterfowl hunting takes place, compared to hunting-free areas. The result of his study:

The flight distance of huntable waterbird populations is 10-12 times greater than that of non-huntable populations in regions with little or no hunting. Measured in square metres, the area without waterbirds in huntable populations is 100 times greater than in non-huntable parts of the world.

As can be seen from historical images, waterfowl hunting probably played an important role in the past in the area that is now Raet National Park. A large number of hunted auks and guillemots indicate that these birds were far more numerous in the past than they are today. Today, there are obviously only a few hunters still active in the national park, and hunting can no longer be considered an important economic or other factor for the region. It should therefore not be too difficult politically to persuade these few hunters to pursue their interest outside the national park.

Not only birdwatchers and photographers would benefit, but also all other visitors to the national park. They would be much less of a disturbance themselves, but could experience a much richer wildlife at closer range. At the same time, the animals would have up to 100 times more space at their disposal, which they could use and live in.

B) Introduction of ‘No-take Zones’ in more than half of the national park.

The underwater world is by far the most important and valuable part of Raet National Park, as can be seen in report 2024-38 from the Institute of Marine Research. This area therefore deserves much more attention. Conservation and research should go hand in hand here. Much of the diversity of life remains undiscovered. The devastating effect of large-scale removal of marine animals and physical damage to the seabed through bottom trawling can only be guessed at.

The fact that even the Ministry of Fisheries has introduced a ban on fishing for cod, which has declined dramatically in local stocks, shows that conservation measures (at least temporarily) are also being used here to rebuild stocks.

The lobster reserve established for research purposes in the Flødevigen area also shows how fishing can benefit from ‘no-take zones’. The ‘spillover effect’ for local lobster fishermen is demonstrated here in an impressive way.

As marine biologists have been able to show in many examples around the world, and as explained in the Institute of Marine Research’s report 2024-30 on Raet National Park, the introduction of no-take zones is likely to have a very positive impact on the diversity of life in the zones and on fishing in the vicinity of the zones.

The most important factor here is that fish and other marine animals grow older and larger in fishing-free zones and produce exponentially more offspring with increasing size, and in some cases also more frequently.

The goal of a ‘true’ national park according to the IUCN criteria, potentially Norway’s first, can be achieved by not taking or harming animals and other natural elements from at least the majority of the national park.

At the same time, we propose dividing the national park into two areas to keep restrictions on local fishermen and recreational fishing at an acceptable level:

- The shelf area on the islands and in the archipelago, which makes up about half of the national park. Here, criteria for particularly valuable areas should be developed in collaboration with research institutes, which can be used to introduce smaller fishing exclusion zones. In most of this inner area of the national park, there is still sufficient space for fishing activities.

- A large, contiguous area extending as a transect across different habitats in deeper marine zones. Here, a basic ban on fishing, primarily bottom trawling, should come into force as soon as possible, and monitoring of the protective effect should be entrusted to marine research institutions from the outset.